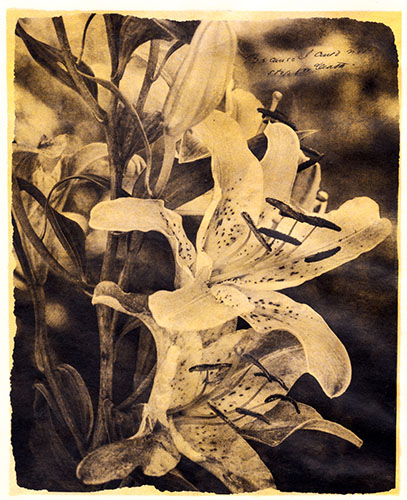

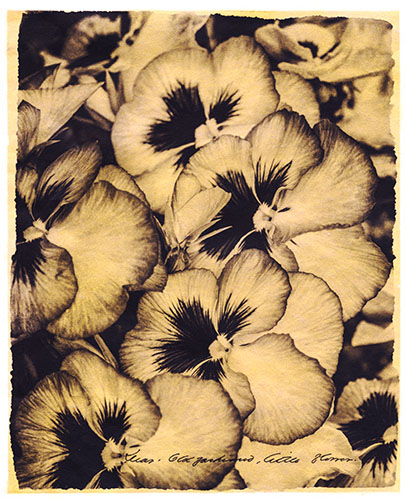

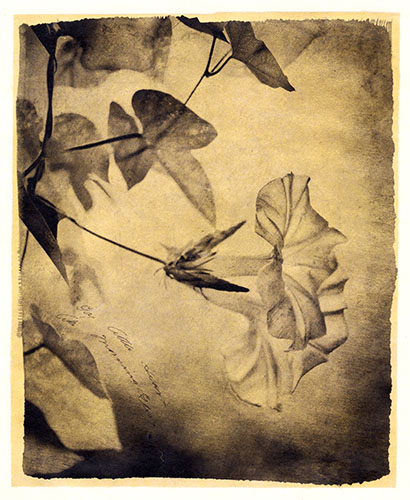

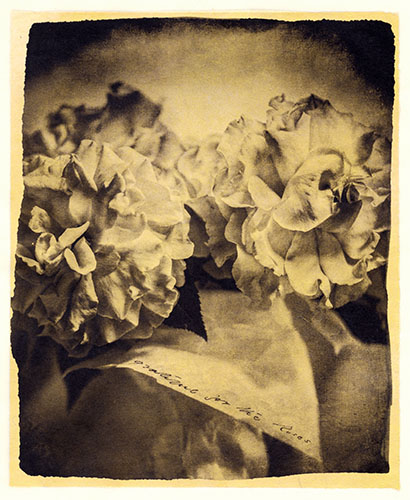

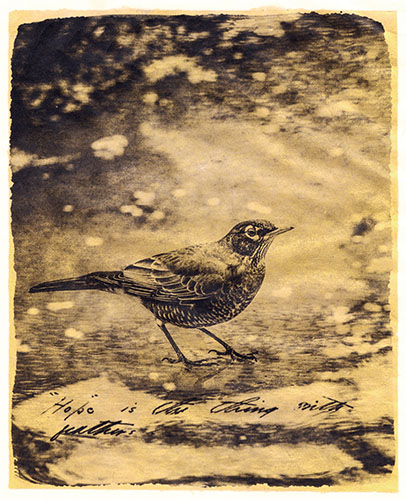

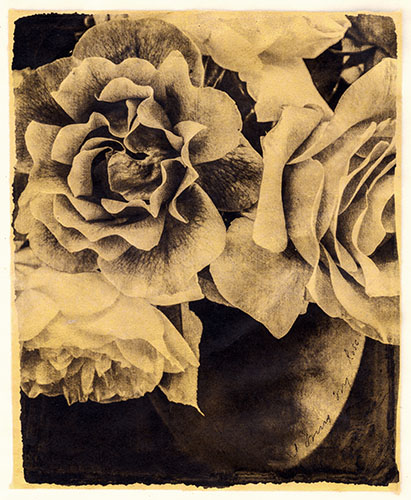

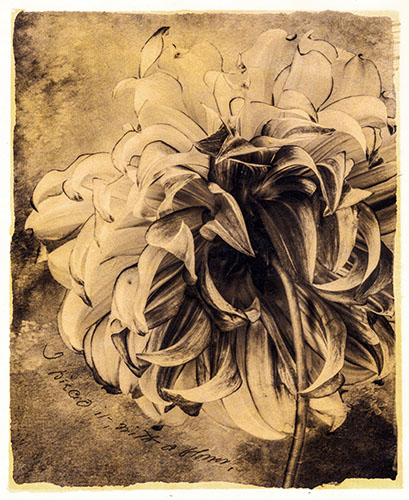

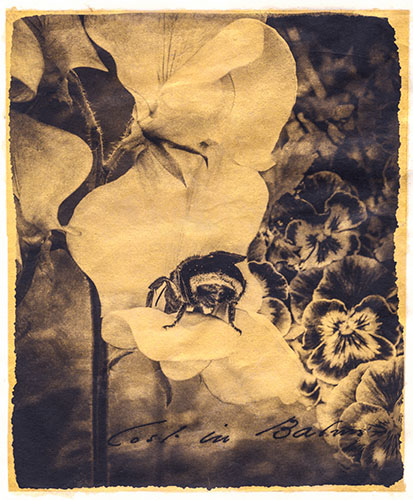

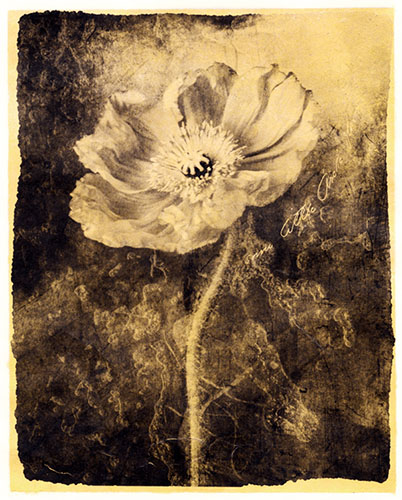

My first photographs were of flowers and I suspect my last will be as well. I have been drawn to gardens and to flowers, their exotic geometry and sensuous rigor, as long as I can remember. It is a rare day that there are no fresh flowers on my breakfast table. I share these feelings with Emily Dickinson, also a devoted gardener and lover of flowers, who often sent bouquets from her garden, accompanied by her poems, to friends and acquaintances.

Dickinson’s poems first captured my imagination in high school—and her grip has never let go. I’m not alone. Her poems are widely admired and her life mythologized. Thousands of books include her poems or analyze them, and recent films star Cynthia Nixon as the talented, reclusive, poet in A Quiet Passionand Molly Shannon as Emily obsessed and in love with her sister-in-law Susan in the comedy, Wild Nights with Emily. A new Apple web series, also a comedy, looks at Emily’s early years and her fight to get her voice heard.

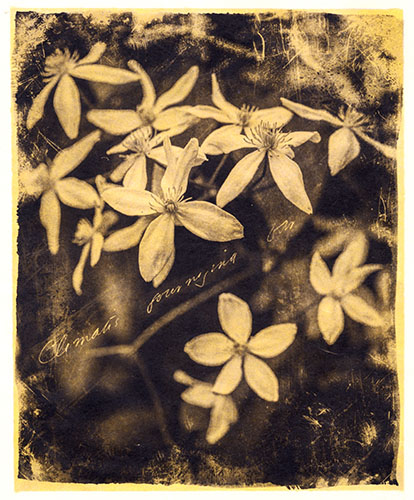

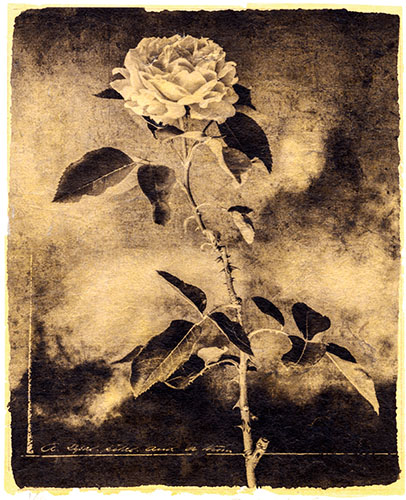

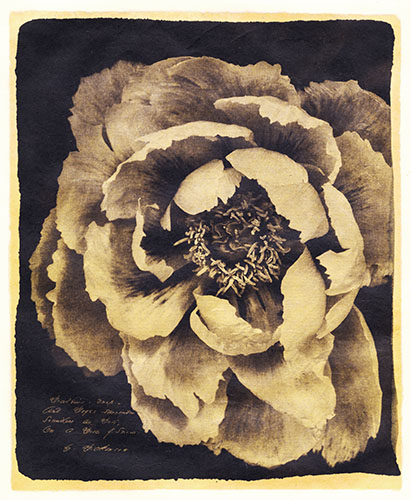

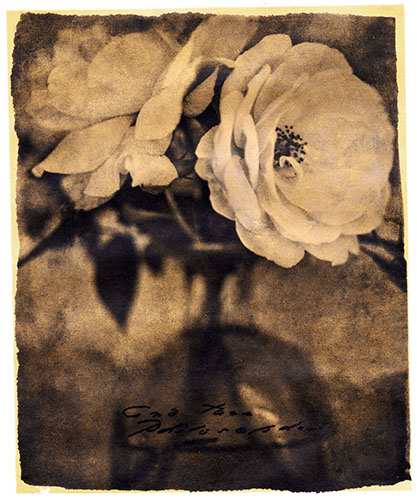

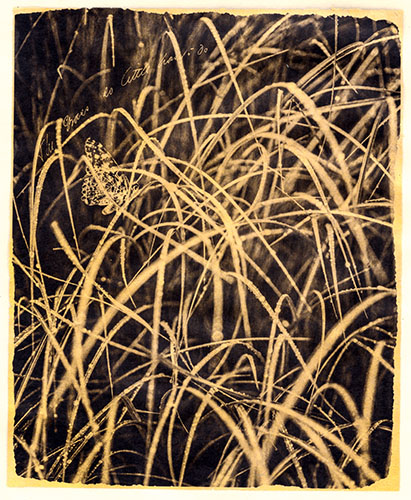

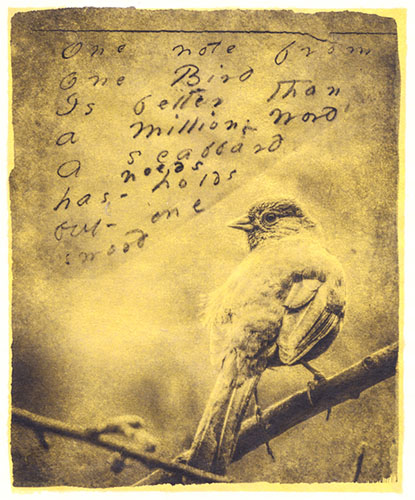

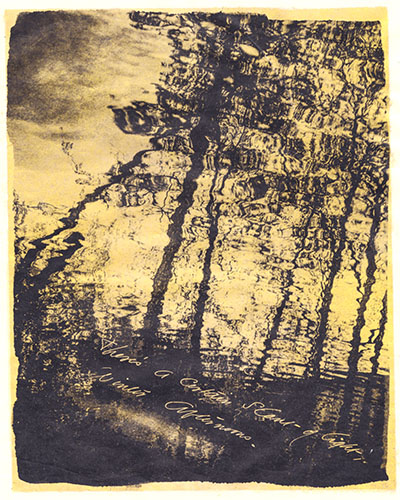

Given that her poetry is unusual in its structure and handling of language—sometimes even opaque—what is it that attracts such devotion? Much is owing to the richness and mystery of her imagery, especially those flowers that become the vivid metaphors for her thoughts on every subject. Her poems were gardens in which she planted the flowers of her imagination. She used the 19th century “language of flowers,” in which an emotion or quality was commonly ascribed to a particular flower, but went beyond it to create visual bouquets of her own meaning. She makes herself the flower in her garden of the poem.

I have tried to capture the spirit and depth of her poetry as embodied in her floral metaphors—the poesy of her posies—by including in her own handwriting the line of a poem, inconspicuously or half hidden, on which my image is based. She wrote almost 1800 poems, adorned with many hundreds of floral references. I had a wealth of inspiration.

The images are printed with platinum/palladium on handmade Japanese gampi paper and backed with gold leaf. The lines of Dickinson’s poems generously provided online in the Emily Dickinson Archive (EDA) are used by permission of Houghton Library of Harvard University and Amherst College Archives & Special Collections, who own the originals.